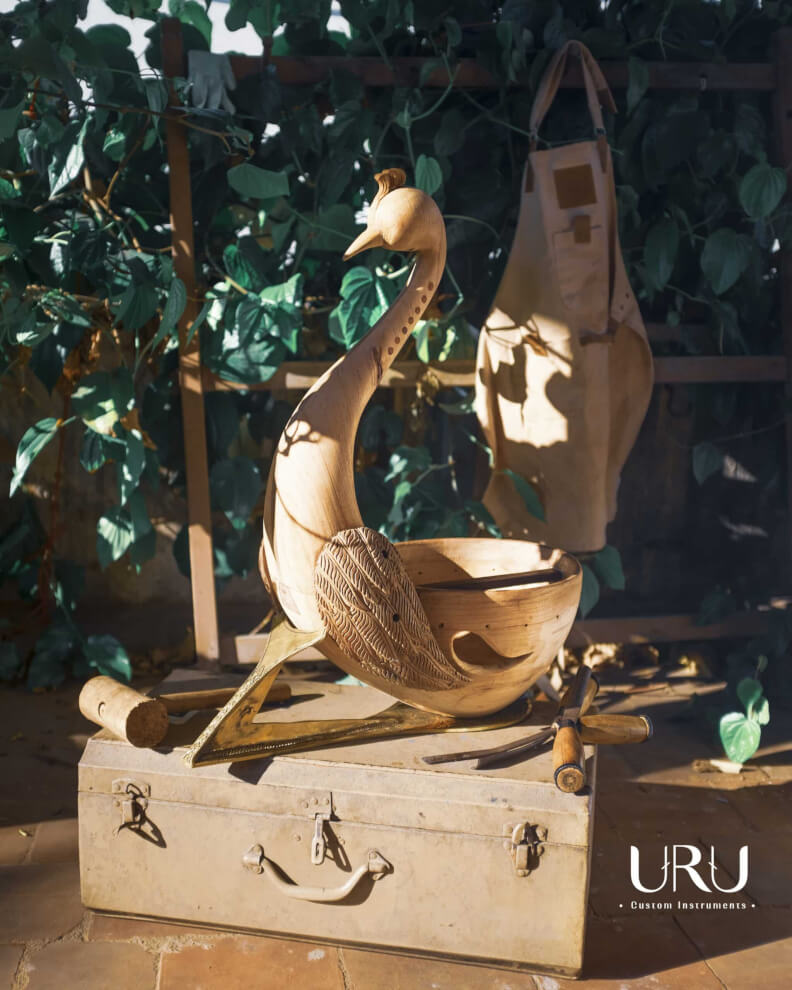

Last year, the yazh, a forgotten instrument from the Sangam period was resurrected in its modern form by a young musician and luthier, Tharun Sekar. Perched on an ornamental brass stand is the head resembling a peacock, carved out of polished red cedar, seamlessly transforming into a slender arching neck that expands at the bottom where two small wings envelop a wooden bowl with goat hide stretched over the opening to make a soundboard.

A few months later, amidst scenic landscapes, we see the frame cut to nimble fingers that gently caress the seven strings affixed between the neck and the taut goat hide to produce the first-ever song recorded with the 2000-year-old harp-like instrument. The song, titled Azhagi, was a collaboration between Tharun, rapper Syan Saheer and artiste Sivasubramanian a.k.a. The Nomad Culture. As a nostalgic undertone envelops the atmosphere, the trio sing about the return of a beautiful and powerful woman from the Sangam period—perhaps a poetic reference to the resurrection of the yazh.

Building the modern yazh was a research-intensive process that involved talking to scholars, scouring through pages of Tamil literature scattered with hints about the mythical instrument and studying representative models locked up in museums. Ancient scriptures claim that the yazh has the sweetest sound. Tharun Sekar’s recording is now validating the claim.

“I grew up listening to the Beatles, Eric Clapton and Jim Morrison,” says Tharun recollecting his earliest musical influences from when he was in high school back in Madurai. As he strummed and experimented with different guitars, there was one that he could not get his hands on—the Hawaiian Lap Steel Guitar. “Back then it wasn’t available anywhere in India. I couldn’t even order it online!” he says. The unavailability of the instrument did not discourage him, rather it intrigued him enough to look up a YouTube video, scout the local markets and contact a handful of online vendors to piece together his own Lap Steel Guitar. “Listening to music being produced from wood that you bought, shaped, sanded and glued together is an entirely different feeling,” he gleams.

The hands-on design experience from his hobby pushed him to pursue a degree in Architecture at Hosur. Every summer he would come back to Madurai and build a new instrument. He was addicted to the process. Tharun’s architectural internship at Auroville was the turning point in his music career. The self-taught luthier decided that he was in the right place to take his passion to the next level. “I was interning at Sacred Groves where we would usually start work early and finish at around 2 pm,” he explains, “After I was done with work, I would go to Svaram (a renown music community in Auroville) and interact with the founder Aurelio.” As a result, Tharun found himself giving a lecture at the weekly Auroville community gathering about his passion for stringed instruments and how he started building them. “I even played the banjo and the ukulele that I built,” he adds. That was when Aurelio introduced Tharun to Erisa Neogy, a luthier with nearly forty years of experience building different types of guitars. An awestruck and delighted Tharun underwent mentorship working in the master luthier’s workshop as an apprentice for six months.

In 2019, Tharun graduated from architecture school and was already performing with bandmate Pravekha Ravichandran, making music under the name Othasevuru. Instead of joining an architecture firm, Tharun moved to Chennai and founded Uru Custom Instruments—derived from the Tamil word ‘uruvam’ which means form. The brand would focus on custom-designing Indian instruments. “After spending nearly seven years building guitars, I realised that Indian instruments weren’t as popular because they did not evolve with time like their western counterparts,” Tharun reveals. While interacting with several people about this, Tharun was introduced to the yazh and was intrigued by the mysterious aura that surrounded it. “From the very beginning, I wanted to make sure that the yazh we built would sound as close to the original as possible while integrating modern elements for easy maintenance.”

Sangam literature did not provide an illustrated user manual to build the yazh. “There would be descriptive paragraphs about how the instrument was played in the court or a chapter about a competition that hints at which materials shouldn’t be used to make the instrument,” the luthier explains with extracts from Civaka Cintamani and Silappatikaram. Tharun made his own modifications as well. “The literature also mentioned that the hide stretched over the basket would have to be removed and heated frequently to tighten it in order to maintain the sound quality. That was one of the mechanisms that we simplified for modern use. The soundboard we make can easily be tightened with a spanner.”

The young luthier did not foresee the scale of the impact his passion project would create. “I did not realise how important this instrument was to so many people!” he exclaims amused. Before he knew it, he started receiving international media coverage, collaboration requests and orders from across the globe. Grammy-winning musicians, Tamil scholars and even art connoisseurs—everyone seemed to want to get their hands on the harp-like instrument that had risen from the ashes.

With the internet as an enabler, the sky was the limit for the young entrepreneur. However, the widescale popularity came with its own challenges. The event of a professor from a renowned university claiming recognition for building the yazh lead Tharun to realise the importance of design protection laws. He took the event as a lesson and immediately registered the design under Uru Custom Instruments.

“Simply building the instrument is not enough. It needs an ecosystem to survive and grow,” adds the musician, “That is why we plan to take classes as well. We are designing the instrument for beginners so that more people will be open to learning it.” Besides this, Tharun has an entire creative production team that is assisting him with the outreach. “We are releasing a documentary at the end of this year about the process of building the yazh,” he explains with a grin, “I am also working on an entire album with about twelve songs composed on the yazh which we will release along with the documentary.”

Uru currently has two junior luthiers assisting Tharun in crafting the instruments. The material is sourced from Munnar, Andaman, Podicherry, Germany and several local markets. “It is also absolutely normal to not find the same material at the same place at a later time,” laughs the luthier describing the excitement involved in scouting around for rare pieces and parts.

While the first yazh took about six months to make, the team now builds about four custom-made yazhs in the same amount of time and has taken up twelve orders (including a custom seven-foot-tall peri yazh with 29 strings) over the last two years. “Mass manufacture is next in the line but we want to test the waters and slowly scale,” says the founder hinting that the Kodambakkam-based studio may even shift base back to Madurai or Theni depending on the scale of manufacture in the years to come.

The custom instrument brand is currently attempting to design and build the different types of yazhs categorised based on the shape and number of strings. “We are still doing R&D and want to specialise in mass manufacturing one instrument before diversifying,” reveals the luthier, “However, we have been working on re-building the Panchamukha Vadyam (a five-faced percussion instrument),” he adds with excitement expecting the first prototype to be ready by the end of this year. This is only the beginning as Uru envisions to pave the way to transforming the musical ecosystem in India by reviving and propagating rare and beginner-friendly Indian instruments.