“There have been two prominent players market for the last decade but the EV market in India is still less than one percent,” the CEO of Raptee Energy, Dinesh Arjun declares, “Why hasn’t the transition happened as yet?”

The Chennai-based startup, Raptee is one among the five hundred players in the increasingly growing electric two-wheeler space. What makes them stand apart? They are designing EVs for the Indian context—one where motorcycles pass hands from one generation to the other with a lifespan of at least twelve years.

Like most other EV origin stories, Raptee was conceived in a garage with two tables. Circa 2018, Dinesh found himself shuttling between his master’s program in the US and his automotive manufacturing businesses in India every month. During these week-long visits to Chennai, he and his junior from college, Keerthivasan Ravi would ideate and build prototypes for what would be their new venture together.

Dinesh had experience in manufacturing and retail in the two-wheeler space. “Motorcycles aren’t the safest mode of transport, but not everyone can afford a car,” says the co-founder as he begins to explain how they intend to bring mobility to a larger audience and eventually create a safer electric automobile ecosystem.

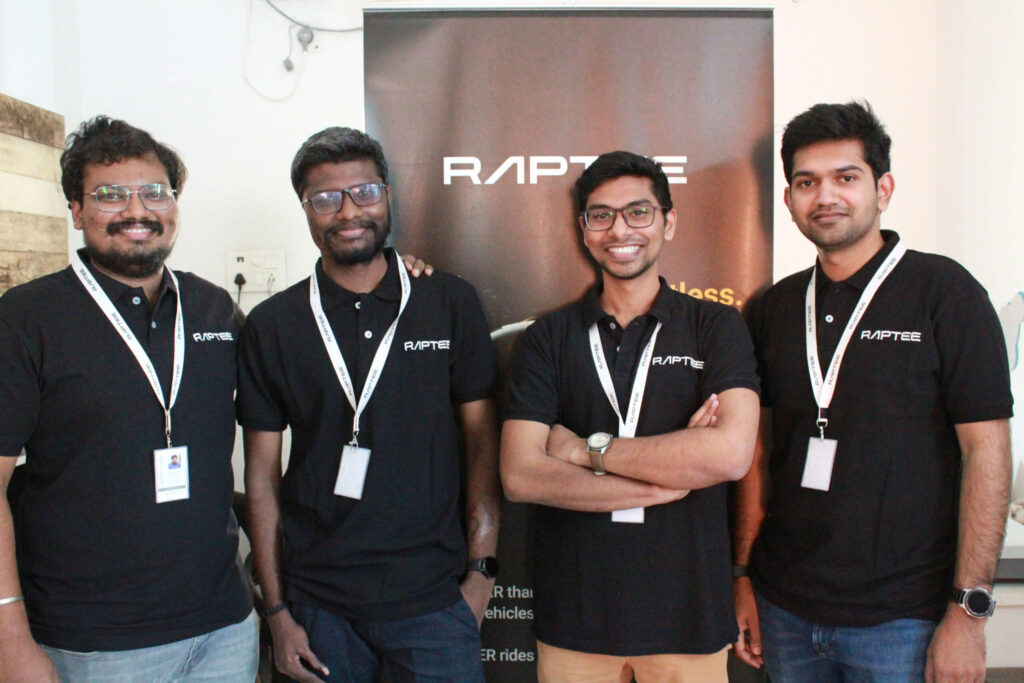

Dinesh and Keerthivasan had mapped out where they would fit in the two-wheeler market. Just as they were structuring their startup for incorporation they onboarded Phunith Kumar and Karthikeyan Adhikesavan.

“We incorporated in the US first, but onboarding investors was difficult without a product,” divulges the co-founder as he enumerates the advantages of moving back home to start the new venture, “The language, lower cost of living and a college ecosystem that is open to collaboration made the move to Chennai a no-brainer.”

The four co-founders were all production engineers by education, nevertheless, they found their niche within the company. Keerthivasan would be the mechanical engineer of the group with a focus on the manufacturing processes, Phunith with his experience as a software engineer at Wipro would take care of testing and cloud computing while Karthikeyan found his place in the electronics. “Well me, I mostly do this,” Dinesh discloses as we break into laughter mid-interview.

None of the co-founders had any experience in automotive design. Recruitment was a challenge. “We used AngelList during our initial days because only a specific group of people interested in the startup ecosystem would apply for jobs through that portal,” says Dinesh. “Today, Raptee has grown into a team of sixty-six which is big for a startup but small for an automotive company,” he adds as he describes the twelve specialised teams within the company.

Raptee was one of the first startups to be incubated in the Anna University Atal Incubation Centre. While that gave it the recognition it needed, the new centre still wasn’t equipped for the new EV company. Raptee moved out from the centre—but not too far in order to easily recruit more students from the university. They found themselves a garage in Ekkattuthangal and eventually rented out the space above it as well, creating a cosy 2,000sqft workspace.

The EV ecosystem in India is competitive. The biggest challenge is to stand apart from the competition, which mostly consists of people who reassemble imported components. “Most southeast Asian electric two-wheelers are inexpensive—around the ten to twenty thousand rupees price range with a maximum speed of 30km/hr,” reveals the co-founder. However, these plastic-bodied vehicles usually have a short lifespan of about two years. The average Indian, on the other hand, is used to the 100cc-150cc bikes. For instance, the Splendour not only has a long lifespan but also can accelerate up to 100km/hr.

For the last two years, Raptee has been working on the architecture of their high-voltage e-motorcycle —designed with metal body panels for durability. “EV shouldn’t be looked at as a compromise in order to become environmentally conscious,” says the co-founder as he lists the advantages of building a motorbike powered by a battery above 200 volts. While the high-voltage e-motorcycle has improved performance and increased reliability, the real edge Raptee has over other EVs is that it does not have to be charged frequently. “There are about twenty-four charging stations in Chennai, so we would not require to invest in infrastructure to build extra charging stations when our product is launched.”

Raptee develops the components and outsources manufacturing to small facilities in Ambattur and Thirumazhisai SIDCO Industrial Estate. An in-house team then works on assembly. The startup has also recently signed an MOU with the Tamil Nadu Government to acquire a 36-acre land parcel to scale manufacture.

Besides the immense support from the state government to gain visibility (which has helped the startup receive funding), Raptee Energy has received grants from the Automotive Research Association of India (ARAI) and the Central Government as it inches closer to its product launch late this year. “The bottleneck is our second round of funding. Turns out making an automobile isn’t as easy,” he chuckles.

As of now, there are three months of booking. The product reveal during the launch will increase that number. The first phase will see limited manufacture of 10,000 units for a period of one year. The initial distribution will be around Chennai, Coimbatore, Bangalore and Kochi. Eighteen months after production, Raptee e-motorcycles will be available pan-India.

India is still sceptical about EV, especially with the news of battery fires. “People understand why some vehicles fail. They also see that there are some plants that are very good at what they do,” he claims, “The best thing about the Indian market is that you can make products in any price range and there will be a population willing to buy it. Sustaining the product is what is most important.”