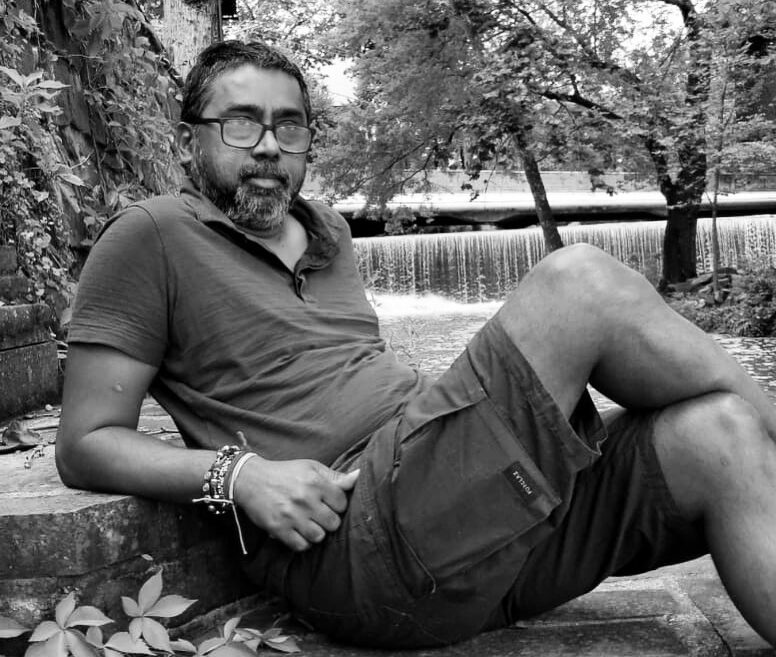

How Shreenie Vasan is setting Tana Bana, the design firm he co-founded, firmly on the global market for surface design patterns, designed in his hometown of Salem, the fifth largest populous state in Tamil Nadu.

“My father, grandfather, and his ancestors were all contract weavers in Salem,” began Shreenie Vasan, co-founder and CEO of Tana Bana, a design agency in Morristown, NJ with a full design studio in Salem. “They depended on the master weavers for business, and had accepted their hand-to-mouth existence as something normal—sometimes, it never made it to the mouth even.”

The young Srinivas Jayapal completed high school and applied to many colleges. One of them, a quite famous one at that, demanded fifteen thousand rupees as a donation. “We didn’t earn that sum in a month, and my father wouldn’t hear of it,” he recalls, “when I found out the Indian Institute of Handloom Technology right in our backyard, and what’s more, they paid a scholarship to fund my education.”

The freshman was exposed to the world of handloom, jacquards, weaves, print, and many other art forms of textile design. “Apart from the fact that all faculty spoke in Hindi, my choice wasn’t too shabby,” he laughs. “And then I discovered that a handloom saree sold for over two hundred thousand rupees—a sum my family wouldn’t make in two years!” That set the young Jayapal thinking about how to formalize his textile weaving skills with design skills, and his search led him to the National Institute of Design, in Ahmedabad.

“That was a completely new world for a country person like me, who lived off three shirts and a pair of jeans. People casually dropped twenty rupees for an afternoon snack at the tea shops outside the campus gates, spoke fluent English, had the best of clothes, shoes, you name it,” recalls Srinivas. “But they all accepted me, and I dove right in.”

The young Salem native spent nearly all his waking hours in the weaving studios, exploring, learning, thirstily drinking in everything the institute could offer. “In those days, unless you knew some of the more famous design houses like Satya Paul or others, there weren’t many who would hire a textile designer—forget hiring, they didn’t even what a textile designer did,” he chortles. “I made my way to one of the largest silk mills in Bangalore (now Benguluru), and joined as a designer, and found to my shock the creative director or the chief designer was the CEO’s wife—who had zero credentials, education, or design sensitivity!”

The company’s owner and wife would travel to all the shows across the globe, shoot pictures of various prints and design elements, and bring back photographs to the office. “We used to wonder—what exactly are we going to do with these? Copy them? Be inspired by them? In some of the photographs, there would the CEO’s wife’s saree in the foreground and a standing lamp in the background. What did that even mean?” laughs Shreenie.

But he stuck to his skills and built the company portfolio of prints, weaves, jacquards, and so on. “There were no discussions, debates, or even any face time with our leadership—we were just given tasks.”

As chance would have it, one of the company clients was a mill based in New Jersey, and they sent their senior designer to the India operations to check out the company. “When Susie Ritchie came to the conference room, the CEO called me in and asked to show her all our design, and looked at her and said, “Check them out and let us know how we can improve things here,” and walked out. Susie spent an hour silently looking at all our work in detail, and finally looked up at me, “Was that a trick question? What am I supposed to be doing here?”

Susie and Srinivas got along famously, and she returned home to ask her company to find him a role. In the same year, Srinivas flew out to work in Absecon in New Jersey. “This was a tremendous learning time for me—I saw how U.S. companies dealt with China, India, Colombia, Vietnam, and all other countries. I worked in the performance textile space—hard-wearing textile spread for airport carpets, theater walls, hospitals, and other such use cases.” In eight years, he grew to become the design director, hit a wall, and noticed the signs of decline in the textile industry.

Furniture companies that would buy textile from them, frames from China, and assemble in a remote Georgia factory now asked the Chinese company to deliver the full chair in a shrink-wrap, boxed, and storage-ready. “In less than two years, we saw almost all mills being impacted,” he recalls.

Shreenie (by now he had shortened his name to make it easier) and Susie quit to start Tana Bana, where they began consulting with textile companies. “Many of them had to send designs in digital formats, and had a tough time to digitize patterns—especially with the accuracy and depth of knowledge only a textile designer could bring,” he fondly remembers. “We bought two computers and rented space in an internet café in Salem, and put two people to work. We trained them over Skype calls, and delivered results that went into production without a flaw.”

From two booths, it quickly became four, then eight, and the duo decided to formally open an India office—atop Shreenie’s ancestral home. “Right from the start, we were quite sure on two absolute non-negotiable hiring considerations: that the person we hire should be the eldest in the family, and half our team will be women.”

The duo hired fine arts graduates from the Kumbakkonam Arts College, and trained them in the niche art and nuances of textile design. “For many, this was their first salaried employment in their family history—mostly from families of farmers or day laborers, and this steady income was a completely new sense of stability,” recalls Shreenie.

Circa 2005, the U.S. removed a prior quota restriction that existed for textile imports into the country, and the Chinese mills simply took over the market. “We Indians didn’t stand a chance in either pricing or delivery quality, and lost a wonderful opportunity,” says Shreenie. “And in the U.S., we saw textile design itself shrink. But Susie and I were always visiting fairs, and noticed that many buyers who came to the European fairs were not always buying fabrics, but a whole lot of surface design ideas—for candle sticks, cushion covers, draperies, you name it.”

Tana Bana was quick to pivot, and invested in training their artists in surface art design.

Today, the design studio serves over 350 global brands, and sells over 1800 patterns every year. “When I am traveling, I make it a point to call my artists in Salem, and video chat with them: See your pattern on the cushion cover of this global brand, selling hundreds of pieces of them! This actual proof of their work delights them no end, and builds enormous pride in them,” says Shreenie.

He has also been investing in people wellness and stability. “Most of our team members live in housing we rent out, and simply walk upstairs to their studio,” he smiles, “and they are my best word-of-mouth recruiters. In a small town in Salem, there is this design studio that trains, pays, takes care of health insurance, groomed bachelors into well-sought spouses, and we are not even heard of—like say a large IT firm.”

Tana Bana is quick to point out two facts of pride: they create beautiful patterns that stand the test of any seasonal collections. “Apply our pattern to a fresh green background, you have the spring collection, switch to an earthy color and the festive season is immediately created,” Shreenie outlines. The second is how they delivery absolutely accurate artwork. “We have yet to receive a customer request for artwork changes—we are 100% accurate the first time.”

Large brands have come to rely on Tana Bana for “creative work in challenging windows.” Clients have called Shreenie in the afternoon for some urgent pattern design, and he has delivered them the next morning for breakfast. “Designed in Salem and displayed everywhere is not a simple claim,” he asserts, “I can challenge any design studio to deliver such work overnight. Most of them work with freelancers or contractors, and cannot step up to the plate. We do.” Shreenie resides in Morristown, New Jersey, and Tana Bana studio employs over 30 people in Salem. “It’s been a fun journey, and we’re just getting started,” he laughs.